A few weeks ago, I sat down on a Saturday afternoon to write a post about the top investing mistakes people make on their journeys.

Now, I am not talking about active investing, trying to time the market, or even join that exclusive club of people who actually beat the market.

We’ve covered all that before.

Instead, I wanted to peel the proverbial onion back a little bit more and cover the “second layer” of investing mistakes.

The kind that wouldn’t necessarily torpedo your journey to financial independence – but could definitely add more than a few years to it.

Alas, the very first topic on that list turned out long enough to merit a separate post on investments and investment vehicles.

Today, let’s come back to the broader topic and cover off a few others.

Buying What You Don’t Know

Let’s start with the cardinal sin of investing:

You should never invest in a financial instrument unless you have a solid understanding of how it works.

If that means you are only sticking to stocks and bonds, then so be it.

You don’t need options, futures, warrants, or any other fancy derivatives to have a well-performing portfolio.

On the contrary, you are probably well-advised to avoid them.

Just ask anyone who loaded up on oil futures in April 2020.

Buying What You “Know”

Popularized by the wildly successful Peter Lynch, “buying what you know” became a mantra for millions of fundamental, value investors.

The idea, of course, being that you focus on shares of companies whose products you use – and like.

Other than the fact that this is as active of an investing strategy as it gets, here are some other reasons why buying what you know is NOT a good idea:

#1: Concentration Risk

Even actively managed portfolios should hold at least 30 different stocks in order to eliminate idiosyncratic risk.

In reality, very few retail investors will be that diversified.

Loading up on shares of just a few companies you “know” can push your portfolio severely out of kilter.

Bad news, because taking a hit on just one investment can decimate your entire portfolio.

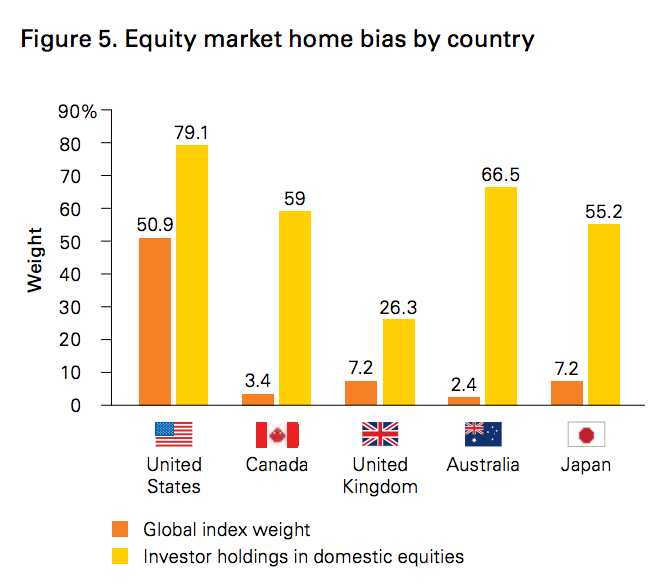

#2: Home Equity Bias

There is strong empirical evidence that investors tend to tilt their portfolios towards domestic equities:

Clearly, this is not the direction you want to go.

However, buying what you know has a real danger of giving you even more exposure to domestic companies as opposed to a nicely diversified, global set of equities.

#3: Your Own Biased Perspective

Sure, you may love the product. But would others agree?

Are there formidable competitors on the horizon, about to blow the proverbial Blackberry out of the water?

Or does the company in question face some deep-rooted internal issues that even a fantastic product lineup won’t fix?

#4: No View On Value

And even if the above doesn’t apply, you simply cannot invest without forming a view on value.

Do you know what the right metric is to value the companies in the sector?

Is it a multiple of revenue, EBITDA, or earnings? Is it some kind of a cash flow measure?

What’s the right baseline to apply the metric to? Is it trailing earnings, next twelve months, or a few years out (for hypergrowth companies)?

Where are the company’s peers trading? And are you cross-checking your valuation with a DCF?

The above is just a subset of very basic analysis you will see in any research report worth the paper it’s printed on.

If you don’t have an answer to these questions, single name investing probably isn’t the best option.

Misunderstanding Dividends

Don’t get me wrong – I totally get the appeal of receiving dividends.

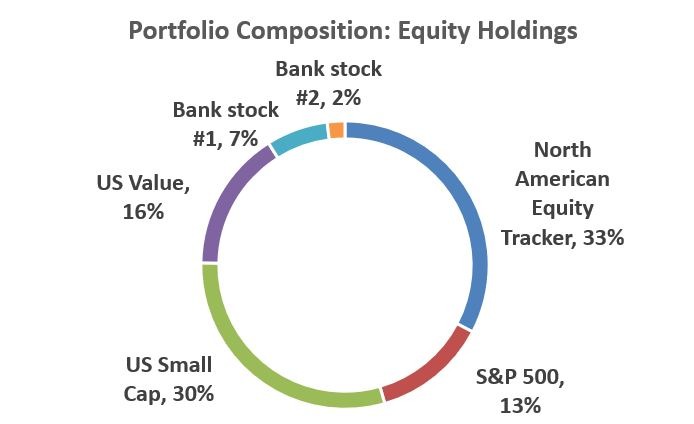

Over the past 12 months, I’ve accumulated a meaningful shareholding in my employer which I plan to liquidate once the share prices rebound:

Those shares happen to pay a dividend, which amounts to a few thousand dollars a quarter.

And yes, it feels good to get that check in the mail (though it still beats me why I get a check instead of a direct deposit into my brokerage account).

So far so good. What I do have a problem with, however, is making dividends the ultimate end goal of investing.

The only goal of investing should be maximizing risk-adjusted returns.

Sure, dividends can help you reach that objective. However, dividends can also be:

- A sign that the company has no better way of deploying cash – so it chooses to return the capital to shareholders instead. This often indicates limited growth prospects for the business.

- A tax-inefficient way to return capital to shareholders. Stock buybacks accomplish the same goal as dividends – all while providing incremental flexibility and (often) much more favorable tax treatment.

- A function of the company’s shareholder register. If many of the shareholders are income-oriented (for example, income funds or retirees), maintaining a dividend is a good way to prevent shareholder churn and share price volatility.

At the extreme end, very high dividend yields (defined as annual dividends divided by share prices) can be a sign that the dividends are about to get cut, which is exactly what happened in the Covid pandemic.

Here are some other hidden dangers of dividend investing you may want to educate yourself about.

Investing In Non-Productive Assets

Bitcoin? Gold? Oil?

I could tell you why this is a bad idea. But why don’t I let Mr. Buffett do the job for me on this one.

It’s taken from his 2011 shareholder letter, hence the examples are a bit dated – but the concept hasn’t lost its punch:

“Today the world’s gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.)

At $1,750 per ounce – gold’s price as I write this – its value would be $9.6 trillion. Call this cube pile A.

Let’s now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all U.S. cropland (400 million acres with an output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world’s most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually).

After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B?

Beyond the staggering valuation given the existing stock of gold, current prices make today’s annual production of gold command about $160 billion.

Buyers – whether jewelry and industrial users, frightened individuals, or speculators – must continually absorb this additional supply to merely maintain an equilibrium at present prices.

A century from now the 400 million acres of farmland will have produced staggering amounts of corn, wheat, cotton, and other crops – and will continue to produce that valuable bounty, whatever the currency may be.

Exxon Mobil will probably have delivered trillions of dollars in dividends to its owners and will also hold assets worth many more trillions (and, remember, you get 16 Exxons).

The 170,000 tons of gold will be unchanged in size and still incapable of producing anything. You can fondle the cube, but it will not respond.

Admittedly, when people a century from now are fearful, it’s likely many will still rush to gold.

I’m confident, however, that the $9.6 trillion current valuation of pile A will compound over the century at a rate far inferior to that achieved by pile B.”

Enough said.

Going “Risk-Off” As You Approach Retirement

In the past, conventional wisdom ran as follows.

About ten years before packing it all in, your financial adviser would slowly start rebalancing your portfolio from equities to bonds.

At age 50, you may have been 20% bonds, 80% equities. By the time you clocked 60, that split would be reversed, perhaps even taken to the extreme case of a 100% bond portfolio.

Safe from the vicissitudes of the stock markets, you retired with a “safe” portfolio yielding a predictable stream of interest payments.

Sadly, with interest rates near zero – and retirement horizons extending both due to growing life expectancies and early retirement plans, that approach no longer works.

The good news is that it has now been proven that an equity portfolio can be just as helpful in supporting you in retirement.

Now, you can debate whether the 4% is the right number to use. Monevator has done a stellar job illustrating why the 4% rule doesn’t work.

What you shouldn’t forget, however, is the following: even at a 4% SWR, while the “failure” rate stands somewhere in the single digits, there’s also a very meaningful chance you (or rather your heirs) will end up with even more money than you started with.

And wouldn’t that be a nice problem to have?

Happy investing!

About Banker On Fire

Enjoyed this post?

Then you may want to sign up for our exclusive updates, delivered straight to your inbox.

You can also follow me on Twitter or Facebook, or share the post using the buttons above.

Banker On FIRE is an M&A (mergers and acquisitions) investment banker. I am passionate about capital markets, behavioural economics, financial independence, and living the best life possible.

Find out more about me and this blog here.

If you are new to investing, here is a good place to start.

For advertising opportunities, please send an email to bankeronfire at gmail dot com

Is this a typo? At age 50, you may have been 80% bonds, 20% equities. By the time you clocked 60, that split would be reversed, perhaps even taken to the extreme case of a 100% bond portfolio.

Yes it is – thanks for spotting! Have fixed now.

I’d say that if you were 65 you would still need to think 20 ahead years to when you would be 85 – how much would things cost then? – what’s the best way to get an above average return so that you can still pay your way? – rising costs don’t stop when you hit retirement – would we still be in a low interest environment?. personally i’ll still be investing into an ISA after i’m 65, and it’ll probably be in equitie,s so

that by my 80’s/90’s it will have grown at, hopefully, a better return than bonds, property, etc. You still have to think long term when you retire.

Spot on. In theory, the SWR can be adjusted for inflation, but as Monevator pointed out in a recent post, headline inflation and our “personal rate of inflation” are two different things.

Then there’s the spending pattern. One of the other readers (Al Cam) helpfully shared a few documents previously that highlight the evolution of spending pattern in retirement, which changes quite significantly depending on age.

Another great post – thanks.

IMO, one of the most common forms of concentration risk relates to your employer (ie salary, share [options], pension payments and/or contributions, and often other perks). In my experience people generally do not recognise the risk they are carrying in this arena until, for some, it is unfortunately too late. I speak from experience – both good and not so good.

Your sentence above “Over the past 12 months, I’ve accumulated a meaningful shareholding in my employer which I plan to liquidate once the share prices rebound:” caught my eye. I too did something very similar. With the benefit of hindsight – my self justification now looks pretty stupid! Due to C-19 I may now be waiting far longer than I could ever have imagined and possibly the share price will never recover. And what, I hear you ask, was my reasoning? Well put simply, it went as follows – I do not have a pressing need for that money and if I had that money what would I do with it. Ho hum….

I am pretty sure I am not the first person to make this type of mistake and the following from Zwecher seems to bear this out “While too many have portfolios that are overweight with company stock, … generally participate in well-diversified retirement plans, hold portfolios outside of the retirement “umbrealla” and are …”

Thanks Al.

You are spot on with the company stock example. To be candid, my other challenge in liquidating it is that my employer makes me jump through numerous hoops (blackout periods, pre-clearing trade requests etc.) before I can sell the stock. Thus, I’ve decided to wait until the next chunk of my portfolio vests in the spring so that I only have to go through this painful process once.

At the same time, I will be the first one to admit that the approach above puts me into active investing theory…. classic example of actions speaking louder than words!

“Even actively managed portfolios should hold at least 30 different stocks in order to eliminate idiosyncratic risk.

In reality, very few retail investors will be that diversified.”

Good article Damian, thank you! Where did you get the “in reality” factoid from? Surely many (most?) retail investors have at least one fund or IT in their portfolio? Each of which normally hold >30 stocks?

Also I still heartily disagree with your constant rubbishing of active investing! I grind my teeth whenever you postulate on this. In the current climate, picking performing funds isn’t rocket science. Perhaps it varies by how hands on one wants to be?

Baillie Gifford or Vanguard …? I know where I’d rather be. Of course things change all the time and it’s that essence of time that might change my mind but I honestly think you could be more open minded on this subject? Yes, overall, “most” active funds aren’t great but in the minority are literally hundreds of fantastic opportunities. Rant over ?

Keep up the work ?

Hey Phil, this comment made my day (honestly). Love the directness and enthusiasm.

In the spirit of candid discussion, a few thoughts below.

On diversification – I had something different in mind. For example, holding 50% of your portfolio in a fund and the other 50% in a single stock theoretically leaves you with 30+ stocks. That’s not really the kind of diversification you want though. What investors should solve for in order to truly eliminate idiosyncratic risk is to have no more than 2-3% of their portfolio in a single stock.

On active investing, where I am coming from is maximizing risk-adjusted returns. Sure, going 100% in on Tesla or Bitcoin 5 years ago would knock passive investing out cold. BUT what is the actual Sharpe ratio of such an investment? Equally, Tesla could well have been Uber (or Microfocus closer to home). Most importantly, the success of an investing approach should be measured over both bull and bear markets, and we haven’t really been in a bear market for 12 years now.

I am totally fine with folks taking 5-10% of their portfolio and going active with it. What I have an issue with is 100% of active investors thinking they can outperform the market while we all know only 50% will – and that 50% will likely be sophisticated quantitative hedge funds than an average joe researching stocks on yahoo finance… Same applies to choosing funds.

Let’s hope we are all still around in ten years so we can go back to this comment and compare notes 🙂 In the meantime, thanks again for the comment – I don’t claim to have a monopoly on truth and love debating these concepts!

Damian,

I am with you on the 2% to 3% threshold.

I actually had my upper threshold set at 5%.

And what is even worse, in the story I relayed above (about concentration risk and employers stock) – this had also previously sailed through that threshold. Did I miss the alert – no, I just effectively ignored it. But, I guess we all make mistakes – even when we set up all the correct risk monitoring.

Medice, cura te ipsum probably better known as Physician heal thyself!

P.S. due to C-19 impact that holding is now somewhat less than 2%.

I guess the real test is what I do when (or indeed if) it ever exceeds 3% again.

Thank you so much for the well-worded response! If my nincomboobery made your day you surely spent that day decorating your loft … as I did!

I actually agree with most of your points but I don’t think one needs a bitcon or Tesla to back up my point. Active investing in one pure sense can be picking a modest diversity of well managed, global funds such as those offered by BG (quite racy?), T Rowe Price (super responsive to changing opportunities and market conditions?) and Rathbone (relatively steady and resilient?). I’d always back such managers over my own judgement on stocks or (crucially) an index. Always. It’s just a matter of picking, sticking with (ish!) and monitoring their performance. Just my opinion ?

Not sure how to prove any of this of course, but I know that lumping all active funds into one blob for analysis won’t cut it.